Magda Pekacka: “We now see in Poland a different generation that wants to live in an open society”

“I hope that with the convergence of Dafne and EFC, we will develop a new quality of philanthropy infrastructure, an organisation that is very inclusive, powerful and visionary. I also hope that this organisation will deal with the topics that are most important for Europeans” said Magda Pekacka, Executive Director of the Polish Donors’ Forum and Vice-Chair of the Dafne Board since 2017. In this interview, Magda shares her thoughts on the perception of the philanthropic sector in Poland, the dynamic growth of corporate philanthropy and how the sector is faring as civil society is put under pressure. She also shares her career journey and passion for live jazz and travelling the world.

By Dr. Hanna Stähle and Karalyn Gardner

How would you characterise public perception of the philanthropic sector in Poland?

“You asked about the philanthropic sector – I don’t think this really exists in the public perception. People don’t really see a difference between the foundation sector and broader civil society.”

Due to the Soviet past in particular, trust for institutions and businesses within Polish society is very low. In the 90s, trust in the philanthropic sector stayed very low because of a number of corruption scandals involving foundations. That is why, when we launched the Polish Donors’ Forum in 2004, one of our first steps was developing a very strict code of conduct. Foundations have to publish their accounts, the rules that govern their grant-making, a list of their grantees so that the general public can understand where the money comes from and where it goes. Since then, the perception of civil society sector has changed. According to public polling, civil society organisations are considered among the most trustworthy, despite smear campaigns which followed the change of government in 2015. But, you asked about the philanthropic sector – I don’t think this really exists in the public perception. People don’t really see a difference between the foundation sector and broader civil society.

How is the sector impacted by the country’s communist past?

All foundations were nationalised during the Soviet period and stopped operating. In 1984, the first legislation governing foundations was passed as the political situation softened a little. Even then, there were only a handful of foundations allowed. The Polish Rural Development Foundation, a founding member of the Polish Donors’ Forum, was the first foundation to operate in this period. Its capital came from the Church which carried out philanthropic activities to encourage rural development through this foundation. After 1989, more foundations started to appear but grant-making foundations, and corporate foundations especially, developed considerably after 2000, and this has accelerated in the last decade.

How do you explain this dynamic growth over the last decade?

It happened quite naturally. For a long time, there was no possibility to establish foundations and other civil society organisations which created an untapped potential within society, mainly for action rather than funding. People wanted to institutionalise their public-purpose activities and they wanted the possibility to access public and private funding which explains the rapid sectoral growth. We currently see the most dynamic growth in the business sector. In the mid 2000s, we were benchmarking based on the other national associations in the region, particularly the Czech Republic, Romania and Slovakia. Poland’s corporate philanthropy sector is developing more rapidly than elsewhere in the region.

“In the mid 2000s, we were benchmarking based on the other national associations in the region, particularly the Czech Republic, Romania and Slovakia. Poland’s corporate philanthropy sector is developing more rapidly than elsewhere in the region.”

What can you tell us about the Polish foundation sector, in terms of numbers and specificities?

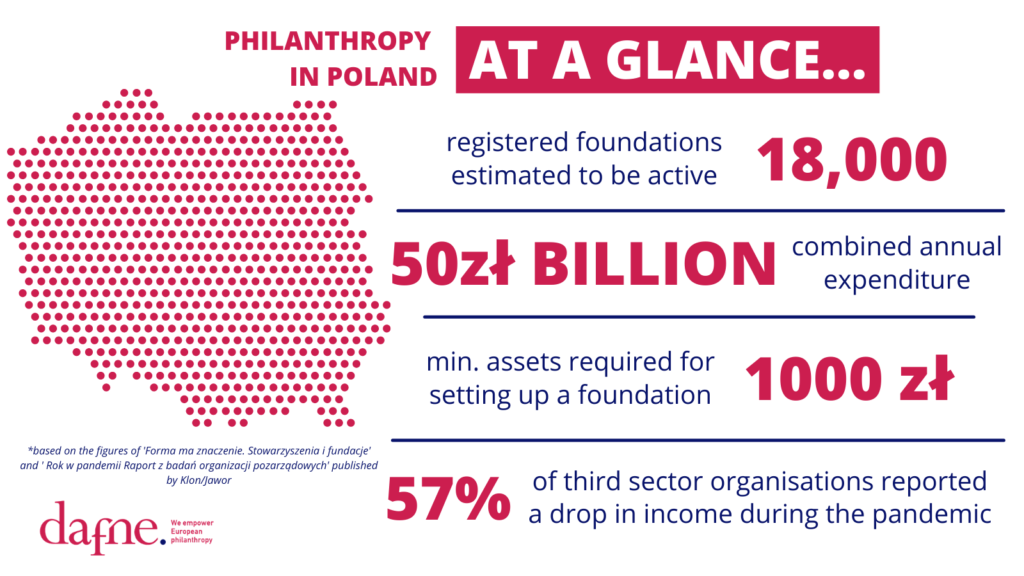

We now have over 26,000 registered foundations in Poland so it is a pretty big sector, of which 18,000 are active according to the research of Klon/Jawor Association. The word ‘foundation’ does not necessarily have the same meaning in Poland as in Western Europe, the majority of foundations are just civil society organisations – they are generally very small and grant-seeking. For many years, it was easier to establish a foundation, which can be founded by an individual, than an association which requires seven people at least (before it was 2016 even 15 people). There are few requirements beyond fulfilling a for-public-benefit purpose but even this is broadly defined. There is no minimum capital required, although in practice, you have to have minimum 1000 zloty, which is just under 220 euros. Registration happens through the courts which is similar to many parts of Europe but the foundation law which governs it is pretty straightforward.

There is only a limited number of grant-making foundations – it is hard to give an exact number as the sector has changed over the last couple of years and it includes more hybrid organisations now. When we started the Donors’ Forum in 2004, all of our founding members were purely grant-makers but now at least half of them, if not more, are carrying out both grant-making and operational programmes. There is no minimum expenditure to qualify as a grant-making foundation, so many foundations consider themselves to be grant-makers but their budget is relatively small.

How did you get involved in the philanthropy sector?

My path was pretty straightforward. I studied sociology at the University of Warsaw and chose some modules in civil society management. These classes interested me the most. At the sames time, I volunteered, carrying out research for some civil society organisations including the Academy for the Development of Philanthropy in Poland and supporting local foodbanks. I quickly understood from this experience that I am more interested in working on structural and sectoral change rather that specific issues. After graduating, I started out working in HR in a company but I didn’t like it – I had a clear idea of what I wanted to do, I wanted to work with civil society. I was closely monitoring vacancies for months. One day, a job ad came up from the Polish Donors’ Forum and I thought “Wow, this is tailor-made for me.” In those seven months of searching, I submitted a single job application and, fortunately, they hired me.

“One day, a job ad came up from the Polish Donors’ Forum and I thought “Wow, this is tailor-made for me.” In those seven months of searching, I submitted a single job application and, fortunately, they hired me.”

What do you consider to be the greatest achievements of the Polish Donors’ Forum?

I think the way in which civil society has built up a trusting relationship with a society that is generally lacking trust.

The Polish Donors’ Forum has also successfully advocated for a very liberal public collection law, which is straightforward and favourable for our sector. We started advocating for this in 2009 and the law was passed in 2014. This is now an important law, particulary not for our members but for the more marginal social movements which are widely supported by individuals and who otherwise would not be able to collect funds. We also participated in shaping a new law on associations which was passed by the Polish Parliament in 2015. This simplified a lot of issues including registration and reduced the number of members necessary to qualify as an association from 15 to 7. Other achievement I’m particulary proud of would be the standards for corporate foudations and a comprehensive quide, which we published in 2015. Thanks to participatory process we managed to create a corporate foundations community, based on trust and collaboration.

We have spoken about the strengthened trust in civil society and other positive achievements yet, on account of political changes, civil society in Poland has known some setbacks over the last six years. What are now the main challenges that you identify?

It is a very complex situation but we do see a lot of negative trends. The government is trying to build up a right-wing civil society, to fit their agenda. In 2016, the government created the National Institute of Freedom which broadly centralises the governments’ funding for civil society. Gradually, the more conservative organisations have grown in strength and now receive the bulk of the funding. These organisations are, for example, patriotic, anti-abortion, pro-family, pro-hunting. Public funding is still the main source of income in the third sector. Many organisations, particularly the more progressive ones, have simply lost their public funding.

“Many organisations, particularly the more progressive ones, have simply lost their public funding.”

It has also been difficult in terms of advocacy and public consultations. Before 2015, there two very active and engaged working groups in Parliament relating to civil society. Now, these are both gone. The processes for public consultation are now very limited and opaque. Generally, the opinions of more progressive civil society organisations are not taken into consideration.

In 2016, the national public TV ran a smear campaign against civil society leaders. This really affected individuals, as well as organisations. There is a climate of anxiety and repression. Now, we receive hoax bomb threats at the office, since I assume we are consider being a part of more progressive group by some radicals. But, there is a remarkable sense of solidarity within the sector but these last years have been exhausting for everybody – it is hard to operate in more marginalised and progressive areas.

Women’s rights is an important topic in Poland, as, last year, the government passed an almost total abortion ban.

As an association, this is not something we speak out on but I have an opinion as a woman and as a citizen. I have participated in various protests. There have been a lot of protests over the past couple years – we have had the issue of the constitutional courts, the judiciary, women’s rights – and definitely, something has changed, the police is more aggressive and you do not feel comfortable. I am still trying to adapt and understand as, for the majority of my life, I did not live in this kind of country. It is really horrible when you go to a protest and you feel so on edge, you have heard stories from the previous day, you know how many people were taken into police custody and that the police drove them to stations outside of Warsaw. If I have a bad day at one of these protests, I think ‘Maybe it’s time to move on but I then have a better day and realise it is not the time to give up.

How can the European and international community support you?

By showing solidarity and speaking up. Financial support is also important as public funding was cut for foundations and organisations that support women’s rights, victims of domestic abuse, as well as climate, rule of law and other causes considered marginal and too progressive. Such organisations have more work to do now but lack financial support. Klon/Jawor Association has carried out their second edition of research into the effects of the pandemic on civil society organisations and the findings are very negative as funding from all types of funders has dropped. I am afraid that this trend will continue.

Last month, the European Commission referred Poland to the European Court of Justice to ensure the independence of Polish judges. Does the EU’s concern about ensuring the rule of law in Poland make you more hopeful?

Yes, this is great – I am glad that this happened. But, the abortion law was the decision of the constitutional court which in practice is illegal but in reality they can make this decision. Hospitals operate according to these decisions as, otherwise, it is too risky. A reaction from the EU is probably the only hope we have right now. I am not 100% happy with the EU’s reaction to Poland in the negotiation of the Recovery and Resilience Plans. We hoped that this would be harsher.

“A reaction from the EU is probably the only hope we have right now.”

What is one thing about Poland that you are optimistic about and would like the readers to know?

I am optimistic about the younger generation. A couple of years ago, I would have said this openness that characterises the youth in the rest of Europe was missing from Poland. At the time, looking at the election results, for example, young voters were not only voting for PiS but for the extreme right and the future they seemed to want for Poland was scary. Many of the people in the streets fighting for women’s rights or for climate come from the generation who could not yet vote last time. We now see in Poland that this is a different generation that wants to live in an open society governed by the rule of law, they want their freedom. I am very optimistic about this change.

“We now see in Poland that this is a different generation that wants to live in an open society governed by the rule of law, they want their freedom. I am very optimistic about this change.”

What have you learned from your Dafne colleagues?

It is so important for me to by part of Dafne, now more than ever! I have this feeling that my country has gradually disconnected from Europe over recent years but I still feel strongly that we are part of Europe. Over the last fifteen years, my Dafne colleagues have provided help, advice, encouragement and expertise whenever I have reached out. This has really inspired me. I really appreciate, alongside the professional support, the human side of Dafne.

What is your vision for the future European philanthropy in the context of the Dafne/EFC convergence?

I hope that with the convergence of Dafne and EFC, we will develop a new quality of philanthropy infrastructure, an organisation that is very inclusive, powerful and visionary. I also hope that this organisation will deal with the topics that are most important for Europeans, such as climate, education and solidarity for countries where things are not going so well. I think that this is a great moment – it is high time to launch this.

What is something your colleagues might not know about you?

I like jazz. I like classical jazz but I love very noisy jazz that is basically improvisation. Before pandemic, I would listen to it live almost every week, since we have quite a vibrant scene in Poland and at least three places in Warsaw that host the top improvising jazz musician from around the globe.

What book would you take with you to a desert island?

To take only one book to a deserted island sounds pretty terrible. When I go away, I like to take many different books with me – I am the kind of person who can read different books at the same time. At the moment, I am reading “Slouching toward Bethlehem” by Joan Didion, a great American novelist. I watched a documentary about her and this inspired me to read her book. One of my favourite recent Polish novels is “Gorzko, gorzko” (Bitterly, bitterly) by Joanna Bator, a feminist writer, which portrays four generations of women based in Silesia, a very diverse, coal-mining region of Poland.

Let’s imagine for a second that the pandemic was over and you could travel freely. Where would you go to first?

I think about this a lot. I would probably go to Mexico, even though I have been there twice. The pandemic makes me miss this kind of travelling the most. Mexico is a very colourful country with open-minded people, always smiling, playing music on the streets. The food is beautiful. I love the diversity there: there are fantastic, colourful cities as well as very remote places in the mountain, jungles, the ocean.

On the other end of the world, my best friend keeps asking me to go to India. I have been there five times now and I feel like I should explore some other destinations. I fell in love with the Ladakh and Kashmiri region, in the Himalayas. This area is extremely beautiful and the people there are so kind, they have an amazing aura. We live in such a fast-paced world, we work a lot and we can be frustrated because we always want to do more but, there, life is much simpler and people are so wise. People are unafraid to ask people, even strangers, big questions like “Are you happy?” and “What makes you happy?”.

So what does make you feel happy?

I adore my friends and I could not imagine my life without them. It is probably one of the things that really stops me moving away from Poland.

Obviously, I love to travel but I love even the parts that put other people off like sitting on a bus for hours on end riding a bumpy road. I feel so privileged that I have time for myself, to see these interesting parts of the world and to connect with different people.

Music, particularly live music, makes me happy and I miss it so much.

Eager to learn more about the philanthropic sector in Poland? Here is some recommended reading:

- A year in a pandemic. NGO Research Report (2020/2021), Klon/Jawor

- Legal Environment for Philanthropy in Poland 2020, Philanthropy Advocacy

- Philanthropy in CEE 2020, Social Impact Alliance for CEE

- Form Matters. Foundations and associations. (2019), Klon/Jawor

- Standards for Corporate Donors (2015), Polish Donors’ Forum